Difference between revisions of "User:Jhurley/sandbox"

(→State of the Practice) |

|||

| (223 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | ==PFAS Destruction by Ultraviolet/Sulfite Treatment== |

| − | + | The ultraviolet (UV)/sulfite based reductive defluorination process has emerged as an effective and practical option for generating hydrated electrons (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) which can destroy [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] in water. It offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction, including significant defluorination, high treatment efficiency for long-, short-, and ultra-short chain PFAS without mass transfer limitations, selective reactivity by hydrated electrons, low energy consumption, low capital and operation costs, and no production of harmful byproducts. A UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor">Haley and Aldrich, Inc. (commercial business), 2024. EradiFluor. [https://www.haleyaldrich.com/about-us/applied-research-program/eradifluor/ Comercial Website]</ref>) has been demonstrated in two field demonstrations in which it achieved near-complete defluorination and greater than 99% destruction of 40 PFAS analytes measured by EPA method 1633. | |

<div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | ||

'''Related Article(s):''' | '''Related Article(s):''' | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| + | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] | ||

| + | *[[PFAS Sources]] | ||

| + | *[[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma]] | ||

| + | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] | ||

| + | *[[Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction]] | ||

| + | '''Contributors:''' John Xiong, Yida Fang, Raul Tenorio, Isobel Li, and Jinyong Liu | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| + | *Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management<ref name="BentelEtAl2019">Bentel, M.J., Yu, Y., Xu, L., Li, Z., Wong, B.M., Men, Y., Liu, J., 2019. Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), pp. 3718-28. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b06648 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06648] [[Media: BentelEtAl2019.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> | ||

| + | *Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies<ref>Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Gao, J., Yu, Y., Men, Y., Gu, C., Liu, J., 2022. Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies. Environmental Science and Technology, 56(6), pp. 3699-3709. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c07608 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07608] [[Media: LiuZEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> | ||

| + | *Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment<ref>Tenorio, R., Liu, J., Xiao, X., Maizel, A., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2020. Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(11), pp. 6957-67. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00961]</ref> | ||

| + | *EradiFluor<sup>TM</sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> | ||

| − | ''' | + | ==Introduction== |

| − | + | The hydrated electron (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) can be described as an electron in solution surrounded by a small number of water molecules<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988">Buxton, G.V., Greenstock, C.L., Phillips Helman, W., Ross, A.B., 1988. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (⋅OH/⋅O-) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 17(2), pp. 513-886. [https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555805 doi: 10.1063/1.555805]</ref>. Hydrated electrons can be produced by photoirradiation of solutes, including sulfite, iodide, dithionite, and ferrocyanide, and have been reported in literature to effectively decompose per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water. The hydrated electron is one of the most reactive reducing species, with a standard reduction potential of about −2.9 volts. Though short-lived, hydrated electrons react rapidly with many species having more positive reduction potentials<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988"/>. | |

| − | + | Among the electron source chemicals, sulfite (SO<sub>3</sub><sup>2−</sup>) has emerged as one of the most effective and practical options for generating hydrated electrons to destroy PFAS in water. The mechanism of hydrated electron production in a sulfite solution under ultraviolet is shown in Equation 1 (UV is denoted as ''hv, SO<sub>3</sub><sup><big>'''•-'''</big></sup>'' is the sulfur trioxide radical anion): | |

| − | + | </br> | |

| − | + | ::<big>'''Equation 1:'''</big> [[File: XiongEq1.png | 200 px]] | |

| − | The | + | The hydrated electron has demonstrated excellent performance in destroying PFAS such as [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)]], [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanoic acid|perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)]]<ref>Gu, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., Han, H., Dong, W., 2017. Hydrated Electron Based Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in the VUV/Sulfite System. Science of The Total Environment, 607-608, pp. 541-48. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197]</ref> and [[Wikipedia: GenX|GenX]]<ref>Bao, Y., Deng, S., Jiang, X., Qu, Y., He, Y., Liu, L., Chai, Q., Mumtaz, M., Huang, J., Cagnetta, G., Yu, G., 2018. Degradation of PFOA Substitute: GenX (HFPO–DA Ammonium Salt): Oxidation with UV/Persulfate or Reduction with UV/Sulfite? Environmental Science and Technology, 52(20), pp. 11728-34. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02172 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02172]</ref>. Mechanisms include cleaving carbon-to-fluorine (C-F) bonds (i.e., hydrogen/fluorine atom exchange) and chain shortening (i.e., [[Wikipedia: Decarboxylation | decarboxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Hydroxylation | hydroxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Elimination reaction | elimination]], and [[Wikipedia: Hydrolysis | hydrolysis]])<ref name="BentelEtAl2019"/>. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Process Description== | |

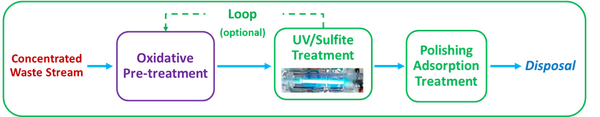

| + | A commercial UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) includes an optional pre-oxidation step to transform PFAS precursors (when present) and a main treatment step to break C-F bonds by UV/sulfite reduction. The effluent from the treatment process can be sent back to the influent of a pre-treatment separation system (such as a [[Wikipedia: Foam fractionation | foam fractionation]], [[PFAS Treatment by Anion Exchange | regenerable ion exchange]], or a [[Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membrane Filtration Systems for PFAS Removal | membrane filtration system]]) for further concentration or sent for off-site disposal in accordance with relevant disposal regulations. A conceptual treatment process diagram is shown in Figure 1. [[File: XiongFig1.png | thumb | left | 600 px | Figure 1: Conceptual Treatment Process for a Concentrated PFAS Stream]]<br clear="left"/> | ||

| − | + | ==Advantages== | |

| − | + | A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by ''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'', low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below: | |

| − | + | *'''High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS:''' While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies<ref>Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452]</ref><ref>Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02158 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158]</ref><ref>Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170]</ref>, the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including [[Wikipedia: Trifluoroacetic acid | trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)]] and [[Wikipedia: Perfluoropropionic acid | perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA)]]. | |

| − | + | *'''High defluorination ratio:''' As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions. | |

| − | + | *'''No harmful byproducts:''' While some oxidative technologies, such as electrochemical oxidation, generate toxic byproducts, including perchlorate, bromate, and chlorate, the UV/sulfite system employs a reductive mechanism and does not generate these byproducts. | |

| − | + | *'''Ambient pressure and low temperature:''' The system operates under ambient pressure and low temperature (<60°C), as it utilizes UV light and common chemicals to degrade PFAS. | |

| − | + | *'''Low energy consumption:''' The electrical energy per order values for the degradation of [[Wikipedia: Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids | perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs)]] by UV/sulfite have been reduced to less than 1.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter under laboratory conditions. The energy consumption is orders of magnitude lower than that for many other destructive PFAS treatment technologies (e.g., [[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO) | supercritical water oxidation]])<ref>Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp. 866-915. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916]</ref>. | |

| − | + | *'''Co-contaminant destruction:''' The UV/sulfite system has also been reported effective in destroying certain co-contaminants in wastewater. For example, UV/sulfite is reported to be effective in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated volatile organic compounds, such as trichloroethene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and vinyl chloride<ref>Jung, B., Farzaneh, H., Khodary, A., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2015. Photochemical degradation of trichloroethylene by sulfite-mediated UV irradiation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 3(3), pp. 2194-2202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026]</ref><ref>Liu, X., Yoon, S., Batchelor, B., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2013. Photochemical degradation of vinyl chloride with an Advanced Reduction Process (ARP) – Effects of reagents and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal, 215-216, pp. 868-875. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086]</ref><ref>Li, X., Ma, J., Liu, G., Fang, J., Yue, S., Guan, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., 2012. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(13), pp. 7342-49. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es3008535 doi: 10.1021/es3008535]</ref><ref>Li, X., Fang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, S., Pan, B., Ma, J., 2014. Kinetics and efficiency of the hydrated electron-induced dehalogenation by the sulfite/UV process. Water Research, 62, pp. 220-228. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051]</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Limitations== | |

| − | * | + | Several environmental factors and potential issues have been identified that may impact the performance of the UV/sulfite treatment system, as listed below. Solutions to address these issues are also proposed. |

| − | + | *Environmental factors, such as the presence of elevated concentrations of natural organic matter (NOM), dissolved oxygen, or nitrate, can inhibit the efficacy of UV/sulfite treatment systems by scavenging available hydrated electrons. Those interferences are commonly managed through chemical additions, reaction optimization, and/or dilution, and are therefore not considered likely to hinder treatment success. | |

| + | *Coloration in waste streams may also impact the effectiveness of the UV/sulfite treatment system by blocking the transmission of UV light, thus reducing the UV lamp's effective path length. To address this, pre-treatment may be necessary to enable UV/sulfite destruction of PFAS in the waste stream. Pre-treatment may include the use of strong oxidants or coagulants to consume or remove UV-absorbing constituents. | ||

| + | *The degradation efficiency is strongly influenced by PFAS molecular structure, with fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS) and [[Wikipedia: Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid | perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS)]] exhibiting greater resistance to degradation by UV/sulfite treatment compared to other PFAS compounds. | ||

| − | + | ==State of the Practice== | |

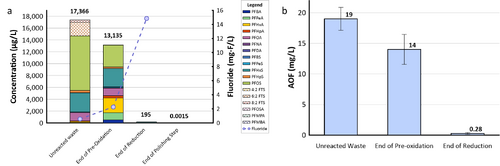

| − | + | [[File: XiongFig2.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 2. Field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> for PFAS destruction in a concentrated waste stream in a Mid-Atlantic Naval Air Station: a) Target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99% of PFAS were destroyed; meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 15 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective PFAS destruction; b) AOF concentrations at each step of the treatment provided additional evidence to show near-complete mineralization of PFAS. Average results from multiple batches of treatment are shown here.]] | |

| − | + | [[File: XiongFig3.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 3. Field demonstration of a treatment train (SAFF + EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) for groundwater PFAS separation and destruction at an Air Force base in California: a) Two main components of the treatment train, i.e. SAFF and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>; b) Results showed the effective destruction of various PFAS in the foam fractionate. The target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99.9% of PFAS were destroyed. Meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 30 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective destruction of PFAS in a foam fractionate concentrate. After a polishing treatment step (GAC) via the onsite groundwater extraction and treatment system, all PFAS were removed to concentrations below their MCLs.]] | |

| − | + | The effectiveness of UV/sulfite technology for treating PFAS has been evaluated in two field demonstrations using the EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> system. Aqueous samples collected from the system were analyzed using EPA Method 1633, the [[Wikipedia: TOP Assay | total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay]], adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF) method, and non-target analysis. A summary of each demonstration and their corresponding PFAS treatment efficiency is provided below. | |

| − | + | *Under the [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)] [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/4c073623-e73e-4f07-a36d-e35c7acc75b6/er21-5152-project-overview Project ER21-5152], a field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was conducted at a Navy site on the east coast, and results showed that the technology was highly effective in destroying various PFAS in a liquid concentrate produced from an ''in situ'' foam fractionation groundwater treatment system. As shown in Figure 2a, total PFAS concentrations were reduced from 17,366 micrograms per liter (µg/L) to 195 µg/L at the end of the UV/sulfite reaction, representing 99% destruction. After the ion exchange resin polishing step, all residual PFAS had been removed to the non-detect level, except one compound (PFOS) reported as 1.5 nanograms per liter (ng/L), which is below the current Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 4 ng/L. Meanwhile, the fluoride concentration increased up to 15 milligrams per liter (mg/L), confirming near complete defluorination. Figure 2b shows the adsorbable organic fluorine results from the same treatment test, which similarly demonstrates destruction of 99% of PFAS. | |

| − | + | *Another field demonstration was completed at an Air Force base in California, where a treatment train combining [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/263f9b50-8665-4ecc-81bd-d96b74445ca2 Surface Active Foam Fractionation (SAFF)] and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was used to treat PFAS in groundwater. As shown in Figure 3, PFAS analytical data and fluoride results demonstrated near-complete destruction of various PFAS. In addition, this demonstration showed: a) high PFAS destruction ratio was achieved in the foam fractionate, even in very high concentration (up to 1,700 mg/L of booster), and b) the effluent from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was sent back to the influent of the SAFF system for further concentration and treatment, resulting in a closed-loop treatment system and no waste discharge from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>. This field demonstration was conducted with the approval of three regulatory agencies (United States Environmental Protection Agency, California Regional Water Quality Control Board, and California Department of Toxic Substances Control). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 103: | Line 58: | ||

==See Also== | ==See Also== | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 11:33, 29 January 2026

PFAS Destruction by Ultraviolet/Sulfite Treatment

The ultraviolet (UV)/sulfite based reductive defluorination process has emerged as an effective and practical option for generating hydrated electrons (eaq- ) which can destroy PFAS in water. It offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction, including significant defluorination, high treatment efficiency for long-, short-, and ultra-short chain PFAS without mass transfer limitations, selective reactivity by hydrated electrons, low energy consumption, low capital and operation costs, and no production of harmful byproducts. A UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluorTM[1]) has been demonstrated in two field demonstrations in which it achieved near-complete defluorination and greater than 99% destruction of 40 PFAS analytes measured by EPA method 1633.

Related Article(s):

- Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

- PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment

- PFAS Sources

- PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma

- Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)

- Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction

Contributors: John Xiong, Yida Fang, Raul Tenorio, Isobel Li, and Jinyong Liu

Key Resources:

- Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management[2]

- Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies[3]

- Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment[4]

- EradiFluorTM[1]

Introduction

The hydrated electron (eaq- ) can be described as an electron in solution surrounded by a small number of water molecules[5]. Hydrated electrons can be produced by photoirradiation of solutes, including sulfite, iodide, dithionite, and ferrocyanide, and have been reported in literature to effectively decompose per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water. The hydrated electron is one of the most reactive reducing species, with a standard reduction potential of about −2.9 volts. Though short-lived, hydrated electrons react rapidly with many species having more positive reduction potentials[5].

Among the electron source chemicals, sulfite (SO32−) has emerged as one of the most effective and practical options for generating hydrated electrons to destroy PFAS in water. The mechanism of hydrated electron production in a sulfite solution under ultraviolet is shown in Equation 1 (UV is denoted as hv, SO3•- is the sulfur trioxide radical anion):

The hydrated electron has demonstrated excellent performance in destroying PFAS such as perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)[6] and GenX[7]. Mechanisms include cleaving carbon-to-fluorine (C-F) bonds (i.e., hydrogen/fluorine atom exchange) and chain shortening (i.e., decarboxylation, hydroxylation, elimination, and hydrolysis)[2].

Process Description

A commercial UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluorTM[1]) includes an optional pre-oxidation step to transform PFAS precursors (when present) and a main treatment step to break C-F bonds by UV/sulfite reduction. The effluent from the treatment process can be sent back to the influent of a pre-treatment separation system (such as a foam fractionation, regenerable ion exchange, or a membrane filtration system) for further concentration or sent for off-site disposal in accordance with relevant disposal regulations. A conceptual treatment process diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Advantages

A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by eaq-, low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below:

- High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS: While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies[8][9][10], the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA).

- High defluorination ratio: As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions.

- No harmful byproducts: While some oxidative technologies, such as electrochemical oxidation, generate toxic byproducts, including perchlorate, bromate, and chlorate, the UV/sulfite system employs a reductive mechanism and does not generate these byproducts.

- Ambient pressure and low temperature: The system operates under ambient pressure and low temperature (<60°C), as it utilizes UV light and common chemicals to degrade PFAS.

- Low energy consumption: The electrical energy per order values for the degradation of perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) by UV/sulfite have been reduced to less than 1.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter under laboratory conditions. The energy consumption is orders of magnitude lower than that for many other destructive PFAS treatment technologies (e.g., supercritical water oxidation)[11].

- Co-contaminant destruction: The UV/sulfite system has also been reported effective in destroying certain co-contaminants in wastewater. For example, UV/sulfite is reported to be effective in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated volatile organic compounds, such as trichloroethene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and vinyl chloride[12][13][14][15].

Limitations

Several environmental factors and potential issues have been identified that may impact the performance of the UV/sulfite treatment system, as listed below. Solutions to address these issues are also proposed.

- Environmental factors, such as the presence of elevated concentrations of natural organic matter (NOM), dissolved oxygen, or nitrate, can inhibit the efficacy of UV/sulfite treatment systems by scavenging available hydrated electrons. Those interferences are commonly managed through chemical additions, reaction optimization, and/or dilution, and are therefore not considered likely to hinder treatment success.

- Coloration in waste streams may also impact the effectiveness of the UV/sulfite treatment system by blocking the transmission of UV light, thus reducing the UV lamp's effective path length. To address this, pre-treatment may be necessary to enable UV/sulfite destruction of PFAS in the waste stream. Pre-treatment may include the use of strong oxidants or coagulants to consume or remove UV-absorbing constituents.

- The degradation efficiency is strongly influenced by PFAS molecular structure, with fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS) and perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS) exhibiting greater resistance to degradation by UV/sulfite treatment compared to other PFAS compounds.

State of the Practice

The effectiveness of UV/sulfite technology for treating PFAS has been evaluated in two field demonstrations using the EradiFluorTM[1] system. Aqueous samples collected from the system were analyzed using EPA Method 1633, the total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay, adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF) method, and non-target analysis. A summary of each demonstration and their corresponding PFAS treatment efficiency is provided below.

- Under the Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP) Project ER21-5152, a field demonstration of EradiFluorTM[1] was conducted at a Navy site on the east coast, and results showed that the technology was highly effective in destroying various PFAS in a liquid concentrate produced from an in situ foam fractionation groundwater treatment system. As shown in Figure 2a, total PFAS concentrations were reduced from 17,366 micrograms per liter (µg/L) to 195 µg/L at the end of the UV/sulfite reaction, representing 99% destruction. After the ion exchange resin polishing step, all residual PFAS had been removed to the non-detect level, except one compound (PFOS) reported as 1.5 nanograms per liter (ng/L), which is below the current Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 4 ng/L. Meanwhile, the fluoride concentration increased up to 15 milligrams per liter (mg/L), confirming near complete defluorination. Figure 2b shows the adsorbable organic fluorine results from the same treatment test, which similarly demonstrates destruction of 99% of PFAS.

- Another field demonstration was completed at an Air Force base in California, where a treatment train combining Surface Active Foam Fractionation (SAFF) and EradiFluorTM[1] was used to treat PFAS in groundwater. As shown in Figure 3, PFAS analytical data and fluoride results demonstrated near-complete destruction of various PFAS. In addition, this demonstration showed: a) high PFAS destruction ratio was achieved in the foam fractionate, even in very high concentration (up to 1,700 mg/L of booster), and b) the effluent from EradiFluorTM[1] was sent back to the influent of the SAFF system for further concentration and treatment, resulting in a closed-loop treatment system and no waste discharge from EradiFluorTM[1]. This field demonstration was conducted with the approval of three regulatory agencies (United States Environmental Protection Agency, California Regional Water Quality Control Board, and California Department of Toxic Substances Control).

References

- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Haley and Aldrich, Inc. (commercial business), 2024. EradiFluor. Comercial Website

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Bentel, M.J., Yu, Y., Xu, L., Li, Z., Wong, B.M., Men, Y., Liu, J., 2019. Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), pp. 3718-28. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06648 Open Access Article

- ^ Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Gao, J., Yu, Y., Men, Y., Gu, C., Liu, J., 2022. Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies. Environmental Science and Technology, 56(6), pp. 3699-3709. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07608 Open Access Article

- ^ Tenorio, R., Liu, J., Xiao, X., Maizel, A., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2020. Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(11), pp. 6957-67. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00961

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Buxton, G.V., Greenstock, C.L., Phillips Helman, W., Ross, A.B., 1988. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (⋅OH/⋅O-) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 17(2), pp. 513-886. doi: 10.1063/1.555805

- ^ Gu, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., Han, H., Dong, W., 2017. Hydrated Electron Based Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in the VUV/Sulfite System. Science of The Total Environment, 607-608, pp. 541-48. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197

- ^ Bao, Y., Deng, S., Jiang, X., Qu, Y., He, Y., Liu, L., Chai, Q., Mumtaz, M., Huang, J., Cagnetta, G., Yu, G., 2018. Degradation of PFOA Substitute: GenX (HFPO–DA Ammonium Salt): Oxidation with UV/Persulfate or Reduction with UV/Sulfite? Environmental Science and Technology, 52(20), pp. 11728-34. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02172

- ^ Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452

- ^ Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158

- ^ Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170

- ^ Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp. 866-915. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916

- ^ Jung, B., Farzaneh, H., Khodary, A., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2015. Photochemical degradation of trichloroethylene by sulfite-mediated UV irradiation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 3(3), pp. 2194-2202. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026

- ^ Liu, X., Yoon, S., Batchelor, B., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2013. Photochemical degradation of vinyl chloride with an Advanced Reduction Process (ARP) – Effects of reagents and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal, 215-216, pp. 868-875. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086

- ^ Li, X., Ma, J., Liu, G., Fang, J., Yue, S., Guan, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., 2012. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(13), pp. 7342-49. doi: 10.1021/es3008535

- ^ Li, X., Fang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, S., Pan, B., Ma, J., 2014. Kinetics and efficiency of the hydrated electron-induced dehalogenation by the sulfite/UV process. Water Research, 62, pp. 220-228. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051