|

|

| (194 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | ==Remediation of Stormwater Runoff Contaminated by Munition Constituents== | + | ==PFAS Destruction by Ultraviolet/Sulfite Treatment== |

| − | Past and ongoing military operations have resulted in contamination of surface soil with [[Munitions Constituents | munition constituents (MC)]], which have human and environmental health impacts. These compounds can be transported off site via stormwater runoff during precipitation events. Technologies to “trap and treat” surface runoff before it enters downstream receiving bodies (e.g., streams, rivers, ponds) (see Figure 1), and which are compatible with ongoing range activities are needed. This article describes a passive and sustainable approach for effective management of munition constituents in stormwater runoff.

| + | The ultraviolet (UV)/sulfite based reductive defluorination process has emerged as an effective and practical option for generating hydrated electrons (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) which can destroy [[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) | PFAS]] in water. It offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction, including significant defluorination, high treatment efficiency for long-, short-, and ultra-short chain PFAS without mass transfer limitations, selective reactivity by hydrated electrons, low energy consumption, low capital and operation costs, and no production of harmful byproducts. A UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor">Haley and Aldrich, Inc. (commercial business), 2024. EradiFluor. [https://www.haleyaldrich.com/about-us/applied-research-program/eradifluor/ Comercial Website]</ref>) has been demonstrated in two field demonstrations in which it achieved near-complete defluorination and greater than 99% destruction of 40 PFAS analytes measured by EPA method 1633. |

| | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> | | <div style="float:right;margin:0 0 2em 2em;">__TOC__</div> |

| | | | |

| | '''Related Article(s):''' | | '''Related Article(s):''' |

| | | | |

| − | *[[Munitions Constituents]] | + | *[[Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)]] |

| | + | *[[PFAS Ex Situ Water Treatment]] |

| | + | *[[PFAS Sources]] |

| | + | *[[PFAS Treatment by Electrical Discharge Plasma]] |

| | + | *[[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO)]] |

| | + | *[[Photoactivated Reductive Defluorination - PFAS Destruction]] |

| | | | |

| | + | '''Contributors:''' John Xiong, Yida Fang, Raul Tenorio, Isobel Li, and Jinyong Liu |

| | | | |

| − | '''Contributor:''' Mark E. Fuller | + | '''Key Resources:''' |

| | + | *Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management<ref name="BentelEtAl2019">Bentel, M.J., Yu, Y., Xu, L., Li, Z., Wong, B.M., Men, Y., Liu, J., 2019. Defluorination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) with Hydrated Electrons: Structural Dependence and Implications to PFAS Remediation and Management. Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), pp. 3718-28. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b06648 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06648] [[Media: BentelEtAl2019.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| | + | *Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies<ref>Liu, Z., Chen, Z., Gao, J., Yu, Y., Men, Y., Gu, C., Liu, J., 2022. Accelerated Degradation of Perfluorosulfonates and Perfluorocarboxylates by UV/Sulfite + Iodide: Reaction Mechanisms and System Efficiencies. Environmental Science and Technology, 56(6), pp. 3699-3709. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c07608 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c07608] [[Media: LiuZEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref> |

| | + | *Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment<ref>Tenorio, R., Liu, J., Xiao, X., Maizel, A., Higgins, C.P., Schaefer, C.E., Strathmann, T.J., 2020. Destruction of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) with UV-Sulfite Photoreductive Treatment. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(11), pp. 6957-67. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c00961 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00961]</ref> |

| | + | *EradiFluor<sup>TM</sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> |

| | | | |

| − | '''Key Resource(s):''' | + | ==Introduction== |

| − | *SERDP Project ER19-1106: Development of Innovative Passive and Sustainable Treatment Technologies for Energetic Compounds in Surface Runoff on Active Ranges

| + | The hydrated electron (''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'' ) can be described as an electron in solution surrounded by a small number of water molecules<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988">Buxton, G.V., Greenstock, C.L., Phillips Helman, W., Ross, A.B., 1988. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (⋅OH/⋅O-) in Aqueous Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 17(2), pp. 513-886. [https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555805 doi: 10.1063/1.555805]</ref>. Hydrated electrons can be produced by photoirradiation of solutes, including sulfite, iodide, dithionite, and ferrocyanide, and have been reported in literature to effectively decompose per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water. The hydrated electron is one of the most reactive reducing species, with a standard reduction potential of about −2.9 volts. Though short-lived, hydrated electrons react rapidly with many species having more positive reduction potentials<ref name="BuxtonEtAl1988"/>. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Background==

| + | Among the electron source chemicals, sulfite (SO<sub>3</sub><sup>2−</sup>) has emerged as one of the most effective and practical options for generating hydrated electrons to destroy PFAS in water. The mechanism of hydrated electron production in a sulfite solution under ultraviolet is shown in Equation 1 (UV is denoted as ''hv, SO<sub>3</sub><sup><big>'''•-'''</big></sup>'' is the sulfur trioxide radical anion): |

| − | ===Surface Runoff Characteristics and Treatment Approaches===

| + | </br> |

| − | [[File: FullerFig1.png | thumb | 400 px | Figure 1. Conceptual model of passive trap and treat approach for MC removal from stormwater runoff]]

| + | ::<big>'''Equation 1:'''</big> [[File: XiongEq1.png | 200 px]] |

| − | During large precipitation events the rate of water deposition exceeds the rate of water infiltration, resulting in surface runoff (also called stormwater runoff). Surface characteristics including soil texture, presence of impermeable surfaces (natural and artificial), slope, and density and type of vegetation all influence the amount of surface runoff from a given land area. The use of passive systems such as retention ponds and biofiltration cells for treatment of surface runoff is well established for urban and roadway runoff. Treatment in those cases is typically achieved by directing runoff into and through a small constructed wetland, often at the outlet of a retention basin, or via filtration by directing runoff through a more highly engineered channel or vault containing the treatment materials. Filtration based technologies have proven to be effective for the removal of metals, organics, and suspended solids<ref>Sansalone, J.J., 1999. In-situ performance of a passive treatment system for metal source control. Water Science and Technology, 39(2), pp. 193-200. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0273-1223(99)00023-2 doi: 10.1016/S0273-1223(99)00023-2]</ref><ref>Deletic, A., Fletcher, T.D., 2006. Performance of grass filters used for stormwater treatment—A field and modelling study. Journal of Hydrology, 317(3-4), pp. 261-275. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.05.021 doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.05.021]</ref><ref>Grebel, J.E., Charbonnet, J.A., Sedlak, D.L., 2016. Oxidation of organic contaminants by manganese oxide geomedia for passive urban stormwater treatment systems. Water Research, 88, pp. 481-491. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.019 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.019]</ref><ref>Seelsaen, N., McLaughlan, R., Moore, S., Ball, J.E., Stuetz, R.M., 2006. Pollutant removal efficiency of alternative filtration media in stormwater treatment. Water Science and Technology, 54(6-7), pp. 299-305. [https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2006.617 doi: 10.2166/wst.2006.617]</ref>.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Surface Runoff on Ranges===

| + | The hydrated electron has demonstrated excellent performance in destroying PFAS such as [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)]], [[Wikipedia:Perfluorooctanoic acid|perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)]]<ref>Gu, Y., Liu, T., Wang, H., Han, H., Dong, W., 2017. Hydrated Electron Based Decomposition of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) in the VUV/Sulfite System. Science of The Total Environment, 607-608, pp. 541-48. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.197]</ref> and [[Wikipedia: GenX|GenX]]<ref>Bao, Y., Deng, S., Jiang, X., Qu, Y., He, Y., Liu, L., Chai, Q., Mumtaz, M., Huang, J., Cagnetta, G., Yu, G., 2018. Degradation of PFOA Substitute: GenX (HFPO–DA Ammonium Salt): Oxidation with UV/Persulfate or Reduction with UV/Sulfite? Environmental Science and Technology, 52(20), pp. 11728-34. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02172 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02172]</ref>. Mechanisms include cleaving carbon-to-fluorine (C-F) bonds (i.e., hydrogen/fluorine atom exchange) and chain shortening (i.e., [[Wikipedia: Decarboxylation | decarboxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Hydroxylation | hydroxylation]], [[Wikipedia: Elimination reaction | elimination]], and [[Wikipedia: Hydrolysis | hydrolysis]])<ref name="BentelEtAl2019"/>. |

| − | [[File: FullerFig2.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 2. Conceptual illustration of munition constituent production and transport on military ranges. Mesoscale residues are qualitatively defined as being easily visible to the naked eye (e.g., from around 50 µm to multiple cm in size) and less likely to be transported by moving water. Microscale residues are defined as <50 µm down to below 1 µm, and more likely to be entrained in, and transported by, moving water as particulates. Blue arrows represent possible water flow paths and include both dissolved and solid phase energetics. The red vertical arrow represents the predominant energetics dissolution process in close proximity to the residues due to precipitation.]]

| |

| − | Surface runoff represents a major potential mechanism through which energetics residues and related materials are transported off site from range soils to groundwater and surface water receptors (Figure 2). This process is particularly important for energetics that are water soluble (e.g., [[Wikipedia: Nitrotriazolone | NTO]] and [[Wikipedia: Nitroguanidine | NQ]]) or generate soluble daughter products (e.g., [[Wikipedia: 2,4-Dinitroanisole | DNAN]] and [[Wikipedia: TNT | TNT]]). While traditional MC such as [[Wikipedia: RDX | RDX]] and [[Wikipedia: HMX | HMX]] have limited aqueous solubility, they also exhibit recalcitrance to degrade under most natural conditions. RDX and [[Wikipedia: Perchlorate | perchlorate]] are frequent groundwater contaminants on military training ranges. While actual field measurements of energetics in surface runoff are limited, laboratory experiments have been performed to predict mobile energetics contamination levels based on soil mass loadings<ref>Cubello, F., Polyakov, V., Meding, S.M., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Dontsova, K., 2024. Movement of TNT and RDX from composition B detonation residues in solution and sediment during runoff. Chemosphere, 350, Article 141023. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.141023 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.141023]</ref><ref>Karls, B., Meding, S.M., Li, L., Polyakov, V., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Dontsova, K., 2023. A laboratory rill study of IMX-104 transport in overland flow. Chemosphere, 310, Article 136866. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136866 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136866] [[Media: KarlsEtAl2023.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref>Polyakov, V., Beal, S., Meding, S.M., Dontsova, K., 2025. Effect of gypsum on transport of IMX-104 constituents in overland flow under simulated rainfall. Journal of Environmental Quality, 54(1), pp. 191-203. [https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20652 doi: 10.1002/jeq2.20652] [[Media: PolyakovEtAl2025.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref>Polyakov, V., Kadoya, W., Beal, S., Morehead, H., Hunt, E., Cubello, F., Meding, S.M., Dontsova, K., 2023. Transport of insensitive munitions constituents, NTO, DNAN, RDX, and HMX in runoff and sediment under simulated rainfall. Science of the Total Environment, 866, Article 161434. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161434 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161434] [[Media: PolyakovEtAl2023.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref>Price, R.A., Bourne, M., Price, C.L., Lindsay, J., Cole, J., 2011. Transport of RDX and TNT from Composition-B Explosive During Simulated Rainfall. In: Environmental Chemistry of Explosives and Propellant Compounds in Soils and Marine Systems: Distributed Source Characterization and Remedial Technologies. American Chemical Society, pp. 229-240. [https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2011-1069.ch013 doi: 10.1021/bk-2011-1069.ch013]</ref>. For example, in a previous small study, MC were detected in surface runoff from an active live-fire range<ref>Fuller, M.E., 2015. Fate and Transport of Colloidal Energetic Residues. Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP), Project ER-1689. [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/10760fd6-fb55-4515-a629-f93c555a92f0 Project Website] [[Media: ER-1689-FR.pdf | Final Report.pdf]]</ref>, and more recent sampling has detected MC in marsh surface water adjacent to the same installation (personal communication). Another recent report from Canada also detected RDX in both surface runoff and surface water at low part per billion levels in a survey of several military demolition sites<ref>Lapointe, M.-C., Martel, R., Diaz, E., 2017. A Conceptual Model of Fate and Transport Processes for RDX Deposited to Surface Soils of North American Active Demolition Sites. Journal of Environmental Quality, 46(6), pp. 1444-1454. [https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.02.0069 doi: 10.2134/jeq2017.02.0069]</ref>. However, overall, data regarding the MC contaminant profile of surface runoff from ranges is very limited, and the possible presence of non-energetic constituents (e.g., metals, binders, plasticizers) in runoff has not been examined. Additionally, while energetics-contaminated surface runoff is an important concern, mitigation technologies specifically for surface runoff have not yet been developed and widely deployed in the field. To effectively capture and degrade MC and associated compounds that are present in surface runoff, novel treatment media are needed to sorb a broad range of energetic materials and to transform the retained compounds through abiotic and/or microbial processes.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Surface runoff of organic and inorganic contaminants from live-fire ranges is a challenging issue for the Department of Defense (DoD). Potentially even more problematic is the fact that inputs to surface waters from large testing and training ranges typically originate from multiple sources, often encompassing hundreds of acres. No available technologies are currently considered effective for controlling non-point source energetics-laden surface runoff. While numerous technologies exist to treat collected explosives residues, contaminated soil and even groundwater, the decentralized nature and sheer volume of military range runoff have precluded the use of treatment technologies at full scale in the field.

| + | ==Process Description== |

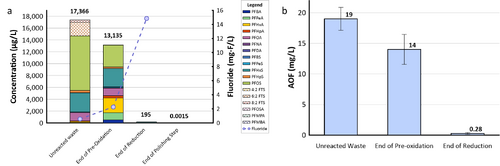

| | + | A commercial UV/sulfite treatment system designed and developed by Haley and Aldrich (EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) includes an optional pre-oxidation step to transform PFAS precursors (when present) and a main treatment step to break C-F bonds by UV/sulfite reduction. The effluent from the treatment process can be sent back to the influent of a pre-treatment separation system (such as a [[Wikipedia: Foam fractionation | foam fractionation]], [[PFAS Treatment by Anion Exchange | regenerable ion exchange]], or a [[Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membrane Filtration Systems for PFAS Removal | membrane filtration system]]) for further concentration or sent for off-site disposal in accordance with relevant disposal regulations. A conceptual treatment process diagram is shown in Figure 1. [[File: XiongFig1.png | thumb | left | 600 px | Figure 1: Conceptual Treatment Process for a Concentrated PFAS Stream]]<br clear="left"/> |

| | | | |

| − | ==Range Runoff Treatment Technology Components== | + | ==Advantages== |

| − | Based on the conceptual foundation of previous research into surface water runoff treatment for other contaminants, with a goal to “trap and treat” the target compounds, the following components were selected for inclusion in the technology developed to address range runoff contaminated with energetic compounds.

| + | A UV/sulfite treatment system offers significant advantages for PFAS destruction compared to other technologies, including high defluorination percentage, high treatment efficiency for short-chain PFAS without mass transfer limitation, selective reactivity by ''e<sub><small>aq</small></sub><sup><big>'''-'''</big></sup>'', low energy consumption, and the production of no harmful byproducts. A summary of these advantages is provided below: |

| | + | *'''High efficiency for short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS:''' While the degradation efficiency for short-chain PFAS is challenging for some treatment technologies<ref>Singh, R.K., Brown, E., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2021. Treatment of PFAS-containing landfill leachate using an enhanced contact plasma reactor. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 408, Article 124452. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124452]</ref><ref>Singh, R.K., Multari, N., Nau-Hix, C., Woodard, S., Nickelsen, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holson, T.M., 2020. Removal of Poly- and Per-Fluorinated Compounds from Ion Exchange Regenerant Still Bottom Samples in a Plasma Reactor. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(21), pp. 13973-80. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c02158 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02158]</ref><ref>Nau-Hix, C., Multari, N., Singh, R.K., Richardson, S., Kulkarni, P., Anderson, R.H., Holsen, T.M., Mededovic Thagard S., 2021. Field Demonstration of a Pilot-Scale Plasma Reactor for the Rapid Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Groundwater. American Chemical Society’s Environmental Science and Technology (ES&T) Water, 1(3), pp. 680-87. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.0c00170]</ref>, the UV/sulfite process demonstrates excellent defluorination efficiency for both short- and ultrashort-chain PFAS, including [[Wikipedia: Trifluoroacetic acid | trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)]] and [[Wikipedia: Perfluoropropionic acid | perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA)]]. |

| | + | *'''High defluorination ratio:''' As shown in Figure 3, the UV/sulfite treatment system has demonstrated near 100% defluorination for various PFAS under both laboratory and field conditions. |

| | + | *'''No harmful byproducts:''' While some oxidative technologies, such as electrochemical oxidation, generate toxic byproducts, including perchlorate, bromate, and chlorate, the UV/sulfite system employs a reductive mechanism and does not generate these byproducts. |

| | + | *'''Ambient pressure and low temperature:''' The system operates under ambient pressure and low temperature (<60°C), as it utilizes UV light and common chemicals to degrade PFAS. |

| | + | *'''Low energy consumption:''' The electrical energy per order values for the degradation of [[Wikipedia: Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids | perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs)]] by UV/sulfite have been reduced to less than 1.5 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per cubic meter under laboratory conditions. The energy consumption is orders of magnitude lower than that for many other destructive PFAS treatment technologies (e.g., [[Supercritical Water Oxidation (SCWO) | supercritical water oxidation]])<ref>Nzeribe, B.N., Crimi, M., Mededovic Thagard, S., Holsen, T.M., 2019. Physico-Chemical Processes for the Treatment of Per- And Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 49(10), pp. 866-915. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2018.1542916]</ref>. |

| | + | *'''Co-contaminant destruction:''' The UV/sulfite system has also been reported effective in destroying certain co-contaminants in wastewater. For example, UV/sulfite is reported to be effective in reductive dechlorination of chlorinated volatile organic compounds, such as trichloroethene, 1,2-dichloroethane, and vinyl chloride<ref>Jung, B., Farzaneh, H., Khodary, A., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2015. Photochemical degradation of trichloroethylene by sulfite-mediated UV irradiation. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 3(3), pp. 2194-2202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026 doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2015.07.026]</ref><ref>Liu, X., Yoon, S., Batchelor, B., Abdel-Wahab, A., 2013. Photochemical degradation of vinyl chloride with an Advanced Reduction Process (ARP) – Effects of reagents and pH. Chemical Engineering Journal, 215-216, pp. 868-875. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.11.086]</ref><ref>Li, X., Ma, J., Liu, G., Fang, J., Yue, S., Guan, Y., Chen, L., Liu, X., 2012. Efficient Reductive Dechlorination of Monochloroacetic Acid by Sulfite/UV Process. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(13), pp. 7342-49. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es3008535 doi: 10.1021/es3008535]</ref><ref>Li, X., Fang, J., Liu, G., Zhang, S., Pan, B., Ma, J., 2014. Kinetics and efficiency of the hydrated electron-induced dehalogenation by the sulfite/UV process. Water Research, 62, pp. 220-228. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.051]</ref>. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Peat=== | + | ==Limitations== |

| − | Previous research demonstrated that a peat-based system provided a natural and sustainable sorptive medium for organic explosives such as HMX, RDX, and TNT, allowing much longer residence times than predicted from hydraulic loading alone<ref>Fuller, M.E., Hatzinger, P.B., Rungkamol, D., Schuster, R.L., Steffan, R.J., 2004. Enhancing the attenuation of explosives in surface soils at military facilities: Combined sorption and biodegradation. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(2), pp. 313-324. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-187 doi: 10.1897/03-187]</ref><ref>Fuller, M.E., Lowey, J.M., Schaefer, C.E., Steffan, R.J., 2005. A Peat Moss-Based Technology for Mitigating Residues of the Explosives TNT, RDX, and HMX in Soil. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal, 14(4), pp. 373-385. [https://doi.org/10.1080/15320380590954097 doi: 10.1080/15320380590954097]</ref><ref name="FullerEtAl2009">Fuller, M.E., Schaefer, C.E., Steffan, R.J., 2009. Evaluation of a peat moss plus soybean oil (PMSO) technology for reducing explosive residue transport to groundwater at military training ranges under field conditions. Chemosphere, 77(8), pp. 1076-1083. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.044 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.08.044]</ref><ref>Hatzinger, P.B., Fuller, M.E., Rungkamol, D., Schuster, R.L., Steffan, R.J., 2004. Enhancing the attenuation of explosives in surface soils at military facilities: Sorption-desorption isotherms. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 23(2), pp. 306-312. [https://doi.org/10.1897/03-186 doi: 10.1897/03-186]</ref><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005">Schaefer, C.E., Fuller, M.E., Lowey, J.M., Steffan, R.J., 2005. Use of Peat Moss Amended with Soybean Oil for Mitigation of Dissolved Explosive Compounds Leaching into the Subsurface: Insight into Mass Transfer Mechanisms. Environmental Engineering Science, 22(3), pp. 337-349. [https://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2005.22.337 doi: 10.1089/ees.2005.22.337]</ref>. Peat moss represents a bioactive environment for treatment of the target contaminants. While the majority of the microbial reactions are aerobic due to the presence of measurable dissolved oxygen in the bulk solution, anaerobic reactions (including methanogenesis) can occur in microsites within the peat. The peat-based substrate acts not only as a long term electron donor as it degrades but also acts as a strong sorbent. This is important in intermittently loaded systems in which a large initial pulse of MC can be temporarily retarded on the peat matrix and then slowly degraded as they desorb<ref name="FullerEtAl2009"/><ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005"/>. This increased residence time enhances the biotransformation of energetics and promotes the immobilization and further degradation of breakdown products. Abiotic degradation reactions are also likely enhanced by association with the organic-rich peat (e.g., via electron shuttling reactions of [[Wikipedia: Humic substance | humics]])<ref>Roden, E.E., Kappler, A., Bauer, I., Jiang, J., Paul, A., Stoesser, R., Konishi, H., Xu, H., 2010. Extracellular electron transfer through microbial reduction of solid-phase humic substances. Nature Geoscience, 3, pp. 417-421. [https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo870 doi: 10.1038/ngeo870]</ref>.

| + | Several environmental factors and potential issues have been identified that may impact the performance of the UV/sulfite treatment system, as listed below. Solutions to address these issues are also proposed. |

| | + | *Environmental factors, such as the presence of elevated concentrations of natural organic matter (NOM), dissolved oxygen, or nitrate, can inhibit the efficacy of UV/sulfite treatment systems by scavenging available hydrated electrons. Those interferences are commonly managed through chemical additions, reaction optimization, and/or dilution, and are therefore not considered likely to hinder treatment success. |

| | + | *Coloration in waste streams may also impact the effectiveness of the UV/sulfite treatment system by blocking the transmission of UV light, thus reducing the UV lamp's effective path length. To address this, pre-treatment may be necessary to enable UV/sulfite destruction of PFAS in the waste stream. Pre-treatment may include the use of strong oxidants or coagulants to consume or remove UV-absorbing constituents. |

| | + | *The degradation efficiency is strongly influenced by PFAS molecular structure, with fluorotelomer sulfonates (FTS) and [[Wikipedia: Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid | perfluorobutanesulfonate (PFBS)]] exhibiting greater resistance to degradation by UV/sulfite treatment compared to other PFAS compounds. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Soybean Oil=== | + | ==State of the Practice== |

| − | Modeling has indicated that peat moss amended with crude soybean oil would significantly reduce the flux of dissolved TNT, RDX, and HMX through the vadose zone to groundwater compared to a non-treated soil (see [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/20e2f05c-fd50-4fd3-8451-ba73300c7531 ESTCP ER-200434]). The technology was validated in field soil plots, showing a greater than 500-fold reduction in the flux of dissolved RDX from macroscale Composition B detonation residues compared to a non-treated control plot<ref name="FullerEtAl2009"/>. Laboratory testing and modeling indicated that the addition of soybean oil increased the biotransformation rates of RDX and HMX at least 10-fold compared to rates observed with peat moss alone<ref name="SchaeferEtAl2005"/>. Subsequent experiments also demonstrated the effectiveness of the amended peat moss material for stimulating perchlorate transformation when added to a highly contaminated soil (Fuller et al., unpublished data). These previous findings clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of peat-based materials for mitigating transport of both organic and inorganic energetic compounds through soil to groundwater.

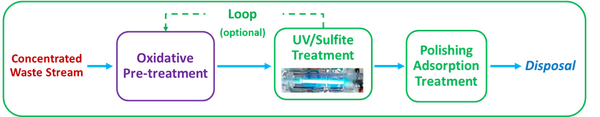

| + | [[File: XiongFig2.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 2. Field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> for PFAS destruction in a concentrated waste stream in a Mid-Atlantic Naval Air Station: a) Target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99% of PFAS were destroyed; meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 15 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective PFAS destruction; b) AOF concentrations at each step of the treatment provided additional evidence to show near-complete mineralization of PFAS. Average results from multiple batches of treatment are shown here.]] |

| − | | + | [[File: XiongFig3.png | thumb | 500 px | Figure 3. Field demonstration of a treatment train (SAFF + EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>) for groundwater PFAS separation and destruction at an Air Force base in California: a) Two main components of the treatment train, i.e. SAFF and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>; b) Results showed the effective destruction of various PFAS in the foam fractionate. The target PFAS at each step of the treatment shows that about 99.9% of PFAS were destroyed. Meanwhile, the final degradation product, i.e., fluoride, increased to 30 mg/L in concentration, demonstrating effective destruction of PFAS in a foam fractionate concentrate. After a polishing treatment step (GAC) via the onsite groundwater extraction and treatment system, all PFAS were removed to concentrations below their MCLs.]] |

| − | ===Biochar===

| + | The effectiveness of UV/sulfite technology for treating PFAS has been evaluated in two field demonstrations using the EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> system. Aqueous samples collected from the system were analyzed using EPA Method 1633, the [[Wikipedia: TOP Assay | total oxidizable precursor (TOP) assay]], adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF) method, and non-target analysis. A summary of each demonstration and their corresponding PFAS treatment efficiency is provided below. |

| − | Recent reports have highlighted additional materials that, either alone, or in combination with electron donors such as peat moss and soybean oil, may further enhance the sorption and degradation of surface runoff contaminants, including both legacy energetics and [[Wikipedia: Insensitive_munition#Insensitive_high_explosives | insensitive high explosives (IHE)]]. For instance, [[Wikipedia: Biochar | biochar]], a type of black carbon, has been shown to not only sorb a wide range of organic and inorganic contaminants including MCs<ref>Ahmad, M., Rajapaksha, A.U., Lim, J.E., Zhang, M., Bolan, N., Mohan, D., Vithanage, M., Lee, S.S., Ok, Y.S., 2014. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere, 99, pp. 19-33. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071]</ref><ref>Mohan, D., Sarswat, A., Ok, Y.S., Pittman, C.U., 2014. Organic and inorganic contaminants removal from water with biochar, a renewable, low cost and sustainable adsorbent – A critical review. Bioresource Technology, 160, pp. 191-202. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.120 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.01.120]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Seo, Y.-D., Jeong, T.-Y., Kim, S.-D., 2018. Sorption of Nitro Explosives to Polymer/Biomass-Derived Biochar. Journal of Environmental Quality, 47(2), pp. 353-360. [https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.09.0357 doi: 10.2134/jeq2017.09.0357]</ref><ref>Xie, T., Reddy, K.R., Wang, C., Yargicoglu, E., Spokas, K., 2015. Characteristics and Applications of Biochar for Environmental Remediation: A Review. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 45(9), pp. 939-969. [https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2014.924180 doi: 10.1080/10643389.2014.924180]</ref>, but also to facilitate their degradation<ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.-J., Chiu, P.C., 2002. Effect of adsorption to elemental iron on the transformation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine in solution. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 21(7), pp. 1384-1389. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620210708 doi: 10.1002/etc.5620210708]</ref><ref>Ye, J., Chiu, P.C., 2006. Transport of Atomic Hydrogen through Graphite and its Reaction with Azoaromatic Compounds. Environmental Science and Technology, 40(12), pp. 3959-3964. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es060038x doi: 10.1021/es060038x]</ref><ref name="OhChiu2009">Oh, S.-Y., Chiu, P.C., 2009. Graphite- and Soot-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene and Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine. Environmental Science and Technology, 43(18), pp. 6983-6988. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es901433m doi: 10.1021/es901433m]</ref><ref name="OhEtAl2013">Oh, S.-Y., Son, J.-G., Chiu, P.C., 2013. Biochar-mediated reductive transformation of nitro herbicides and explosives. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 32(3), pp. 501-508. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2087 doi: 10.1002/etc.2087] [[Media: OhEtAl2013.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref name="XuEtAl2010">Xu, W., Dana, K.E., Mitch, W.A., 2010. Black Carbon-Mediated Destruction of Nitroglycerin and RDX by Hydrogen Sulfide. Environmental Science and Technology, 44(16), pp. 6409-6415. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es101307n doi: 10.1021/es101307n]</ref><ref>Xu, W., Pignatello, J.J., Mitch, W.A., 2013. Role of Black Carbon Electrical Conductivity in Mediating Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (RDX) Transformation on Carbon Surfaces by Sulfides. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(13), pp. 7129-7136. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es4012367 doi: 10.1021/es4012367]</ref>. Depending on the source biomass and [[Wikipedia: Pyrolysis| pyrolysis]] conditions, biochar can possess a high [[Wikipedia: Specific surface area | specific surface area]] (on the order of several hundred m<small><sup>2</sup></small>/g)<ref>Zhang, J., You, C., 2013. Water Holding Capacity and Absorption Properties of Wood Chars. Energy and Fuels, 27(5), pp. 2643-2648. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ef4000769 doi: 10.1021/ef4000769]</ref><ref>Gray, M., Johnson, M.G., Dragila, M.I., Kleber, M., 2014. Water uptake in biochars: The roles of porosity and hydrophobicity. Biomass and Bioenergy, 61, pp. 196-205. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.12.010 doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.12.010]</ref> and hence a high sorption capacity. Biochar and other black carbon also exhibit especially high affinity for [[Wikipedia: Nitro compound | nitroaromatic compounds (NACs)]] including TNT and 2,4-dinitrotoluene (DNT)<ref>Sander, M., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Characterization of Charcoal Adsorption Sites for Aromatic Compounds: Insights Drawn from Single-Solute and Bi-Solute Competitive Experiments. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(6), pp. 1606-1615. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es049135l doi: 10.1021/es049135l]</ref><ref name="ZhuEtAl2005">Zhu, D., Kwon, S., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Adsorption of Single-Ring Organic Compounds to Wood Charcoals Prepared Under Different Thermochemical Conditions. Environmental Science and Technology 39(11), pp. 3990-3998. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es050129e doi: 10.1021/es050129e]</ref><ref name="ZhuPignatello2005">Zhu, D., Pignatello, J.J., 2005. Characterization of Aromatic Compound Sorptive Interactions with Black Carbon (Charcoal) Assisted by Graphite as a Model. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(7), pp. 2033-2041. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0491376 doi: 10.1021/es0491376]</ref>. This is due to the strong [[Wikipedia: Pi-interaction | ''π-π'' electron donor-acceptor interactions]] between electron-rich graphitic domains in black carbon and the electron-deficient aromatic ring of the NAC<ref name="ZhuEtAl2005"/><ref name="ZhuPignatello2005"/>. These characteristics make biochar a potentially effective, low cost, and sustainable sorbent for removing MC and other contaminants from surface runoff and retaining them for subsequent degradation ''in situ''.

| + | *Under the [https://serdp-estcp.mil/ Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP)] [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/4c073623-e73e-4f07-a36d-e35c7acc75b6/er21-5152-project-overview Project ER21-5152], a field demonstration of EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was conducted at a Navy site on the east coast, and results showed that the technology was highly effective in destroying various PFAS in a liquid concentrate produced from an ''in situ'' foam fractionation groundwater treatment system. As shown in Figure 2a, total PFAS concentrations were reduced from 17,366 micrograms per liter (µg/L) to 195 µg/L at the end of the UV/sulfite reaction, representing 99% destruction. After the ion exchange resin polishing step, all residual PFAS had been removed to the non-detect level, except one compound (PFOS) reported as 1.5 nanograms per liter (ng/L), which is below the current Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 4 ng/L. Meanwhile, the fluoride concentration increased up to 15 milligrams per liter (mg/L), confirming near complete defluorination. Figure 2b shows the adsorbable organic fluorine results from the same treatment test, which similarly demonstrates destruction of 99% of PFAS. |

| − | | + | *Another field demonstration was completed at an Air Force base in California, where a treatment train combining [https://serdp-estcp.mil/projects/details/263f9b50-8665-4ecc-81bd-d96b74445ca2 Surface Active Foam Fractionation (SAFF)] and EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was used to treat PFAS in groundwater. As shown in Figure 3, PFAS analytical data and fluoride results demonstrated near-complete destruction of various PFAS. In addition, this demonstration showed: a) high PFAS destruction ratio was achieved in the foam fractionate, even in very high concentration (up to 1,700 mg/L of booster), and b) the effluent from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/> was sent back to the influent of the SAFF system for further concentration and treatment, resulting in a closed-loop treatment system and no waste discharge from EradiFluor<sup><small>TM</small></sup><ref name="EradiFluor"/>. This field demonstration was conducted with the approval of three regulatory agencies (United States Environmental Protection Agency, California Regional Water Quality Control Board, and California Department of Toxic Substances Control). |

| − | Furthermore, black carbon such as biochar can promote abiotic and microbial transformation reactions by facilitating electron transfer. That is, biochar is not merely a passive sorbent for contaminants, but also a redox mediator for their degradation. Biochar can promote contaminant degradation through two different mechanisms: electron conduction and electron storage<ref>Sun, T., Levin, B.D.A., Guzman, J.J.L., Enders, A., Muller, D.A., Angenent, L.T., Lehmann, J., 2017. Rapid electron transfer by the carbon matrix in natural pyrogenic carbon. Nature Communications, 8, Article 14873. [https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14873 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14873] [[Media: SunEtAl2017.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | First, the microscopic graphitic regions in biochar can adsorb contaminants like NACs strongly, as noted above, and also conduct reducing equivalents such as electrons and atomic hydrogen to the sorbed contaminants, thus promoting their reductive degradation. This catalytic process has been demonstrated for TNT, DNT, RDX, HMX, and [[Wikipedia: Nitroglycerin | nitroglycerin]]<ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Chiu, P.C., 2002. Graphite-Mediated Reduction of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene with Elemental Iron. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(10), pp. 2178-2184. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es011474g doi: 10.1021/es011474g]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.J., Chiu, P.C., 2004. Reduction of Nitroglycerin with Elemental Iron: Pathway, Kinetics, and Mechanisms. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(13), pp. 3723-3730. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es0354667 doi: 10.1021/es0354667]</ref><ref>Oh, S.-Y., Cha, D.K., Kim, B.J., Chiu, P.C., 2005. Reductive transformation of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine, octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine, and methylenedinitramine with elemental iron. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 24(11), pp. 2812-2819. [https://doi.org/10.1897/04-662R.1 doi: 10.1897/04-662R.1]</ref><ref name="OhChiu2009"/><ref name="XuEtAl2010"/> and is expected to occur also for IHE including DNAN and NTO.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Second, biochar contains in its structure abundant redox-facile functional groups such as [[Wikipedia: Quinone | quinones]] and [[Wikipedia: Hydroquinone | hydroquinones]], which are known to accept and donate electrons reversibly. Depending on the biomass and pyrolysis temperature, certain biochar can possess a rechargeable electron storage capacity (i.e., reversible electron accepting and donating capacity) on the order of several millimoles e<small><sup>–</sup></small>/g<ref>Klüpfel, L., Keiluweit, M., Kleber, M., Sander, M., 2014. Redox Properties of Plant Biomass-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar). Environmental Science and Technology, 48(10), pp. 5601-5611. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es500906d doi: 10.1021/es500906d]</ref><ref>Prévoteau, A., Ronsse, F., Cid, I., Boeckx, P., Rabaey, K., 2016. The electron donating capacity of biochar is dramatically underestimated. Scientific Reports, 6, Article 32870. [https://doi.org/10.1038/srep32870 doi: 10.1038/srep32870] [[Media: PrevoteauEtAl2016.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref><ref>Xin, D., Xian, M., Chiu, P.C., 2018. Chemical methods for determining the electron storage capacity of black carbon. MethodsX, 5, pp. 1515-1520. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2018.11.007 doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2018.11.007] [[Media: XinEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Article.pdf]]</ref>. This means that when "charged", biochar can provide electrons for either abiotic or biotic degradation of reducible compounds such as MC. The abiotic reduction of DNT and RDX mediated by biochar has been demonstrated<ref name="OhEtAl2013"/> and similar reactions are expected to occur for DNAN and NTO as well. Recent studies have shown that the electron storage capacity of biochar is also accessible to microbes. For example, soil bacteria such as [[Wikipedia: Geobacter | Geobacter]] and [[Wikipedia: Shewanella | Shewanella]] species can utilize oxidized (or "discharged") biochar as an electron acceptor for the oxidation of organic substrates such as lactate and acetate<ref>Kappler, A., Wuestner, M.L., Ruecker, A., Harter, J., Halama, M., Behrens, S., 2014. Biochar as an Electron Shuttle between Bacteria and Fe(III) Minerals. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 1(8), pp. 339-344. [https://doi.org/10.1021/ez5002209 doi: 10.1021/ez5002209]</ref><ref name="SaquingEtAl2016">Saquing, J.M., Yu, Y.-H., Chiu, P.C., 2016. Wood-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar) as a Microbial Electron Donor and Acceptor. Environmental Science and Technology Letters, 3(2), pp. 62-66. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354 doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00354]</ref> and reduced (or "charged") biochar as an electron donor for the reduction of nitrate<ref name="SaquingEtAl2016"/>. This is significant because, through microbial access of stored electrons in biochar, contaminants that do not sorb strongly to biochar can still be degraded.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Similar to nitrate, perchlorate and other relatively water-soluble energetic compounds (e.g., NTO and NQ) may also be similarly transformed using reduced biochar as an electron donor. Unlike other electron donors, biochar can be recharged through biodegradation of organic substrates<ref name="SaquingEtAl2016"/> and thus can serve as a long-lasting sorbent and electron repository in soil. Similar to peat moss, the high porosity and surface area of biochar not only facilitate contaminant sorption but also create anaerobic reducing microenvironments in its inner pores, where reductive degradation of energetic compounds can take place.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Other Sorbents===

| |

| − | Chitin and unmodified cellulose were predicted by [[Wikipedia: Density functional theory | Density Functional Theory]] methods to be favorable for absorption of NTO and NQ, as well as the legacy explosives<ref>Todde, G., Jha, S.K., Subramanian, G., Shukla, M.K., 2018. Adsorption of TNT, DNAN, NTO, FOX7, and NQ onto Cellulose, Chitin, and Cellulose Triacetate. Insights from Density Functional Theory Calculations. Surface Science, 668, pp. 54-60. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2017.10.004 doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2017.10.004] [[Media: ToddeEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>. Cationized cellulosic materials (e.g., cotton, wood shavings) have been shown to effectively remove negatively charged energetics like perchlorate and NTO from solution<ref name="FullerEtAl2022">Fuller, M.E., Farquharson, E.M., Hedman, P.C., Chiu, P., 2022. Removal of munition constituents in stormwater runoff: Screening of native and cationized cellulosic sorbents for removal of insensitive munition constituents NTO, DNAN, and NQ, and legacy munition constituents HMX, RDX, TNT, and perchlorate. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 424(C), Article 127335. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127335 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127335] [[Media: FullerEtAl2022.pdf | Open Access Manuscript.pdf]]</ref>. A substantial body of work has shown that modified cellulosic biopolymers can also be effective sorbents for removing metals from solution<ref>Burba, P., Willmer, P.G., 1983. Cellulose: a biopolymeric sorbent for heavy-metal traces in waters. Talanta, 30(5), pp. 381-383. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-9140(83)80087-3 doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(83)80087-3]</ref><ref>Brown, P.A., Gill, S.A., Allen, S.J., 2000. Metal removal from wastewater using peat. Water Research, 34(16), pp. 3907-3916. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00152-4 doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00152-4]</ref><ref>O’Connell, D.W., Birkinshaw, C., O’Dwyer, T.F., 2008. Heavy metal adsorbents prepared from the modification of cellulose: A review. Bioresource Technology, 99(15), pp. 6709-6724. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.036 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.036]</ref><ref>Wan Ngah, W.S., Hanafiah, M.A.K.M., 2008. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater by chemically modified plant wastes as adsorbents: A review. Bioresource Technology, 99(10), pp. 3935-3948. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.011 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.06.011]</ref> and therefore will also likely be applicable for some of the metals that may be found in surface runoff at firing ranges.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Technology Evaluation==

| |

| − | Based on the properties of the target munition constituents, a combination of materials was expected to yield the best results to facilitate the sorption and subsequent biotic and abiotic degradation of the contaminants.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Sorbents===

| |

| − | The materials screened included [[Wikipedia: Sphagnum | Sphagnum peat moss]], primarily for sorption of HMX, RDX, TNT, and DNAN, as well as [[Wikipedia: Cationization of cotton | cationized cellulosics]] for removal of perchlorate and NTO. The cationized cellulosics that were examined included: pine sawdust, pine shavings, aspen shavings, cotton linters (fine, silky fibers which adhere to cotton seeds after ginning), [[Wikipedia: Chitin | chitin]], [[Wikipedia: Chitosan | chitosan]], burlap (landscaping grade), [[Wikipedia: Coir | coconut coir]], raw cotton, raw organic cotton, cleaned raw cotton, cotton fabric, and commercially cationized fabrics.

| |

| − | | |

| − | As shown in Table 1 (Fuller et al., 2022), batch sorption testing indicated that a combination of Sphagnum peat moss and cationized pine shavings provided good removal of both the neutral organic energetics (HMX, RDX, TNT, DNAN) as well as the negatively charged energetics (perchlorate, NTO).

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Ecological Screening Levels===

| |

| − | Most peer-reviewed literature and regulatory-based environmental quality benchmarks have been developed using data for PFOS and PFOA; however, other select PFAAs have been evaluated for potential effects to aquatic receptors<ref name="ITRC2023"/><ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/><ref name="ConderEtAl2020"/>. USEPA has developed water quality criteria for aquatic life<ref name="USEPA2022"> United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2022. Fact Sheet: Draft 2022 Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (PFOS)). Office of Water, EPA 842-D-22-005. [[Media: USEPA2022.pdf | Fact Sheet]]</ref><ref name="USEPA2024c">United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2024. Final Freshwater Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria and Acute Saltwater Aquatic Life Benchmark for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). Office of Water, EPA-842-R-24-002. [[Media: USEPA2024c.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="USEPA2024d">United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2024. Final Freshwater Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria and Acute Saltwater Aquatic Life Benchmark for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS). Office of Water, EPA-842-R-24-003. [[Media: USEPA2024d.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> for PFOA and PFOS. Following extensive reviews of the peer-reviewed literature, Zodrow ''et al.''<ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/> used the USEPA Great Lakes Initiative methodology<ref>United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2012. Water Quality Guidance for the Great Lakes System. Part 132. [https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2013-title40-vol23/CFR-2013-title40-vol23-part132 Government Website] [[Media: CFR-2013-title40-vol23-part132.pdf | Part132.pdf]]</ref> to calculate acute and chronic screening levels for aquatic life for 23 PFAS. The Argonne National Laboratory has also developed Ecological Screening Levels for multiple PFAS<ref name="GrippoEtAl2024">Grippo, M., Hayse, J., Hlohowskyj, I., Picel, K., 2024. Derivation of PFAS Ecological Screening Values - Update. Argonne National Laboratory Environmental Science Division. [[Media: GrippoEtAl2024.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref>. In contrast to surface water aquatic life benchmarks, sediment benchmark values are limited. For terrestrial systems, screening levels for direct exposure of soil plants and invertebrates to PFAS in soils have been developed for multiple AFFF-related PFAS<ref name="ConderEtAl2020"/><ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/>, and the Canadian Council of Ministers of Environment developed several draft thresholds protective of direct toxicity of PFOS in soil<ref>Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME), 2021. Canadian Soil and Groundwater Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Environmental and Human Health, Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS). [[Media: CCME2018.pdf | Open Access Government Document]]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Wildlife screening levels for abiotic media are back-calculated from food web models developed for representative receptors. Both Zodrow ''et al.''<ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/> and Grippo ''et al.''<ref name="GrippoEtAl2024"/> include the development of risk-based screening levels for wildlife. The Michigan Department of Community Health<ref>Dykema, L.D., 2015. Michigan Department of Community Health Final Report, USEPA Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) Project, Measuring Perfluorinated Compounds in Michigan Surface Waters and Fish. Grant GL-00E01122. [https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/MDCH_GL-00E01122-0_Final_Report_493494_7.pdf Free Download] [[Media: MDCH_Geart_Lakes_PFAS.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> derived a provisional PFOS surface water value for avian and mammalian wildlife. In California, the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board developed terrestrial habitat soil ecological screening levels based on values developed in Zodrow ''et al.''<ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/>. For PFOS only, a dietary screening level (i.e. applicable to the concentration of PFAS measured in dietary items) has been developed for mammals at 4.6 micrograms per kilogram (μg/kg) wet weight (ww), and for avians at 8.2 μg/kg ww<ref>Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2018. Federal Environmental Quality Guidelines, Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS). [[Media: ECCC2018.pdf | Repoprt.pdf]]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Approaches for Evaluating Exposures and Effects in AFFF Site Environmental Risk Assessment: Human Health==

| |

| − | Exposure pathways and effects for select PFAS are well understood, such that standard human health risk assessment approaches can be used to quantify risks for populations relevant to a site. Human health exposures via drinking water have been the focus in risk assessments and investigations at PFAS sites<ref>Post, G.B., Cohn, P.D., Cooper, K.R., 2012. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), an emerging drinking water contaminant: A critical review of recent literature. Environmental Research, 116, pp. 93-117. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2012.03.007 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.03.007]</ref><ref>Guelfo, J.L., Marlow, T., Klein, D.M., Savitz, D.A., Frickel, S., Crimi, M., Suuberg, E.M., 2018. Evaluation and Management Strategies for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Drinking Water Aquifers: Perspectives from Impacted U.S. Northeast Communities. Environmental Health Perspectives,126(6), 13 pages. [https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP2727 doi: 10.1289/EHP2727] [[Media: GuelfoEtAl2018.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. Risk assessment approaches for PFAS in drinking water follow typical, well-established drinking water risk assessment approaches for chemicals as detailed in regulatory guidance documents for various jurisdictions.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Incidental exposures to soil and dusts for PFAS can occur during a variety of soil disturbance activities, such as gardening and digging, hand-to-mouth activities, and intrusive groundwork by industrial or construction workers. As detailed by the ITRC<ref name="ITRC2023"/>, many US states and USEPA have calculated risk-based screening levels for these soil and drinking water pathways (and many also include dermal exposures to soils) using well-established risk assessment guidance.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Field and laboratory studies have shown that some PFCAs and PFSAs bioaccumulate in fish and other aquatic life at rates that could result in relevant dietary PFAS exposures for consumers of fish and other seafood<ref>Martin, J.W., Mabury, S.A., Solomon, K.R., Muir, D.C., 2003. Dietary accumulation of perfluorinated acids in juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 22(1), pp.189-195. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620220125 doi: 10.1002/etc.5620220125]</ref><ref>Martin, J.W., Mabury, S.A., Solomon, K.R., Muir, D.C., 2003. Bioconcentration and tissue distribution of perfluorinated acids in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 22(1), pp.196-204. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620220126 doi: 10.1002/etc.5620220126]</ref><ref>Chen, F., Gong, Z., Kelly, B.C., 2016. Bioavailability and bioconcentration potential of perfluoroalkyl-phosphinic and -phosphonic acids in zebrafish (Danio rerio): Comparison to perfluorocarboxylates and perfluorosulfonates. Science of The Total Environment, 568, pp. 33-41. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.215 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.215]</ref><ref>Fang, S., Zhang, Y., Zhao, S., Qiang, L., Chen, M., Zhu, L., 2016. Bioaccumulation of per fluoroalkyl acids including the isomers of perfluorooctane sulfonate in carp (Cyprinus carpio) in a sediment/water microcosm. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 35(12), pp. 3005-3013. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3483 doi: 10.1002/etc.3483]</ref><ref>Bertin, D., Ferrari, B.J.D. Labadie, P., Sapin, A., Garric, J., Budzinski, H., Houde, M., Babut, M., 2014. Bioaccumulation of perfluoroalkyl compounds in midge (Chironomus riparius) larvae exposed to sediment. Environmental Pollution, 189, pp. 27-34. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2014.02.018 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.02.018]</ref><ref>Bertin, D., Labadie, P., Ferrari, B.J.D., Sapin, A., Garric, J., Geffard, O., Budzinski, H., Babut. M., 2016. Potential exposure routes and accumulation kinetics for poly- and perfluorinated alkyl compounds for a freshwater amphipod: Gammarus spp. (Crustacea). Chemosphere, 155, pp. 380-387. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.04.006 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.04.006]</ref><ref>Dai, Z., Xia, X., Guo, J., Jiang, X., 2013. Bioaccumulation and uptake routes of perfluoroalkyl acids in Daphnia magna. Chemosphere, 90(5), pp.1589-1596. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.08.026 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.08.026]</ref><ref>Prosser, R.S., Mahon, K., Sibley, P.K., Poirier, D., Watson-Leung, T. 2016. Bioaccumulation of perfluorinated carboxylates and sulfonates and polychlorinated biphenyls in laboratory-cultured Hexagenia spp., Lumbriculus variegatus and Pimephales promelas from field-collected sediments. Science of The Total Environment, 543(A), pp. 715-726. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.062 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.062]</ref><ref>Rich, C.D., Blaine, A.C., Hundal, L., Higgins, C., 2015. Bioaccumulation of Perfluoroalkyl Acids by Earthworms (Eisenia fetida) Exposed to Contaminated Soils. Environmental Science and Technology, 49(2) pp. 881-888. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es504152d doi: 10.1021/es504152d]</ref><ref>Muller, C.E., De Silva, A.O., Small, J., Williamson, M., Wang, X., Morris, A., Katz, S., Gamberg, M., Muir, D.C.G., 2011. Biomagnification of Perfluorinated Compounds in a Remote Terrestrial Food Chain: Lichen–Caribou–Wolf. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(20), pp. 8665-8673. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es201353v doi: 10.1021/es201353v]</ref>. In addition to fish, terrestrial wildlife can accumulate contaminants from impacted sites, resulting in potential exposures to consumers of wild game<ref name="ConderEtAl2021"/>. Additionally, exposures can occur though consumption of homegrown produce or agricultural products that originate from areas irrigated with PFAS-impacted groundwater, or that are amended with biosolids that contain PFAS, or that contain soils that were directly affected by PFAS releases<ref>Brown, J.B, Conder, J.M., Arblaster, J.A., Higgins, C.P., 2020. Assessing Human Health Risks from Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS)-Impacted Vegetable Consumption: A Tiered Modeling Approach. Environmental Science and Technology, 54(23), pp. 15202-15214. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c03411 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c03411] [[Media: BrownEtAl2020.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref>. Multiple studies have found PFAS can be taken up by plants from soil porewater<ref>Blaine, A.C., Rich, C.D., Hundal, L.S., Lau, C., Mills, M.A., Harris, K.M., Higgins, C.P., 2013. Uptake of Perfluoroalkyl Acids into Edible Crops via Land Applied Biosolids: Field and Greenhouse Studies. Environmental Science and Technology, 47(24), pp. 14062-14069. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es403094q doi: 10.1021/es403094q] [https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-11/documents/508_pfascropuptake.pdf Free Download from epa.gov]</ref><ref>Blaine, A.C., Rich, C.D., Sedlacko, E.M., Hyland, K.C., Stushnoff, C., Dickenson, E.R.V., Higgins, C.P., 2014. Perfluoroalkyl Acid Uptake in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and Strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) Irrigated with Reclaimed Water. Environmental Science and Technology, 48(24), pp. 14361-14368. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es504150h doi: 10.1021/es504150h]</ref><ref>Ghisi, R., Vamerali, T., Manzetti, S., 2019. Accumulation of perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) in agricultural plants: A review. Environmental Research, 169, pp. 326-341. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.10.023 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.10.023]</ref>, and livestock can accumulate PFAS from drinking water and/or feed<ref>van Asselt, E.D., Kowalczyk, J., van Eijkeren, J.C.H., Zeilmaker, M.J., Ehlers, S., Furst, P., Lahrssen-Wiederhold, M., van der Fels-Klerx, H.J., 2013. Transfer of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) from contaminated feed to dairy milk. Food Chemistry, 141(2), pp.1489-1495. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.035 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.035]</ref>. Thus, when PFAS are present in surface water bodies where fishing or shellfish harvesting occurs or terrestrial areas where produce is grown or game is hunted, the bioaccumulation of PFAS into dietary items can be an important pathway for human exposure.

| |

| − | | |

| − | PFAAs such as PFOA and PFOS are not expected to volatilize from PFAS-impacted environmental media<ref name="USEPA2016a"/><ref name="USEPA2016b"/> such as soil and groundwater, which are the primary focus of most site-specific risk assessments. In contrast to non-volatile PFAAs, fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs) are among the more widely studied of the volatile PFAS. FTOHs are transient in the atmosphere with a lifetime of 20 days<ref>Ellis, D.A., Martin, J.W., De Silva, A.O., Mabury, S.A., Hurley, M.D., Sulbaek Andersen, M.P., Wallington, T.J., 2004. Degradation of Fluorotelomer Alcohols: A Likely Atmospheric Source of Perfluorinated Carboxylic Acids. Environmental Science and Technology, 38(12), pp. 3316-3321. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es049860w doi: 10.1021/es049860w]</ref>. At most AFFF sites under evaluation, AFFF releases have occurred many years before such that FTOH may no longer be present. As such, the current assumption is that volatile PFAS, such as FTOHs historically released at the site, will have transformed to stable, low-volatility PFAS, such as PFAAs in soil or groundwater, or will they have diffused to the outdoor atmosphere. There is no evidence that FTOHs or other volatile PFAS are persistent in groundwater or soils such that they present an indoor vapor intrusion pathway risk concern as observed for chlorinated solvents. Ongoing research continues for the vapor pathway<ref name="ITRC2023"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | General and site-specific human health exposure pathways and risk assessment methods as outlined by USEPA<ref>United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1989. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund: Volume I, Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part A). Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, EPA/540/1-89/002. [https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=10001FQY.txt Free Download] [[Media: USEPA1989.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref><ref name="USEPA1997">United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1997. Ecological Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund: Process for Designing and Conducting Ecological Risk Assessments, Interim Final. Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, EPA 540-R-97-006. [http://semspub.epa.gov/src/document/HQ/157941 Free Download] [[Media: EPA540-R-97-006.pdf | Report.pdf]]</ref> can be applied to PFAS risk assessments for which human health toxicity values have been developed. Additionally, for risk assessments with dietary exposures of PFAS, standard risk assessment food web modeling can be used to develop initial estimates of dietary concentrations which can be confirmed with site-specific tissue sampling programs.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Approaches for Evaluating Exposures and Effects in AFFF Site Environmental Risk Assessment: Ecological==

| |

| − | Information available currently on exposures and effects of PFAS in ecological receptors indicate that the PFAS ecological risk issues at most sites are primarily associated with risks to vertebrate wildlife. Avian and mammalian wildlife are relatively sensitive to PFAS, and dietary intake via bioaccumulation in terrestrial and aquatic food webs can result in exposures that are dominated by the more accumulative PFAS<ref name="LarsonEtAl2018">Larson, E.S., Conder, J.M., Arblaster, J.A., 2018. Modeling avian exposures to perfluoroalkyl substances in aquatic habitats impacted by historical aqueous film forming foam releases. Chemosphere, 201, pp. 335-341. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.004 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.004]</ref><ref name="ConderEtAl2020"/><ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/>. Direct toxicity to aquatic life (e.g., fish, pelagic life, benthic invertebrates, and aquatic plants) can occur from exposure to sediment and surface water at effected sites. For larger areas, surface water concentrations associated with adverse effects to aquatic life are generally higher than those that could result in adverse effects to aquatic-dependent wildlife. Soil invertebrates and plants are generally less sensitive, with risk-based concentrations in soil being much higher than those associated with potential effects to terrestrial wildlife<ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Aquatic life are exposed to PFAS through direct exposure in surface water and sediment. Ecological risk assessment approaches for PFAS for aquatic life follow standard risk assessment approaches. The evaluation of potential risks for aquatic life with direct exposure to PFAS in environmental media relies on comparing concentrations in external exposure media to protective, media-specific benchmarks, including the aquatic life risk-based screening levels discussed above<ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/><ref name="USEPA2024a">United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 2024. National Recommended Water Quality Criteria - Aquatic Life Criteria Table. [https://www.epa.gov/wqc/national-recommended-water-quality-criteria-aquatic-life-criteria-table USEPA Website]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | When an area at the point of PFAS release is an industrial setting which does not feature favorable habitats for terrestrial and aquatic-dependent wildlife, the transport mechanisms may allow PFAS to travel offsite. If offsite or downgradient areas contain ecological habitat, then PFAS transported to these areas are expected to pose the highest risk potential to wildlife, particularly those areas that feature aquatic habitat<ref>Ahrens, L., Bundschuh, M., 2014. Fate and effects of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: A review. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 33(9), pp. 1921-1929. [https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.2663 doi: 10.1002/etc.2663] [[Media: AhrensBundschuh2014.pdf | Open Access Article]]</ref><ref name="LarsonEtAl2018"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Wildlife receptors, specifically birds and mammals, are typically exposed to PFAS through uptake from dietary sources such as plants and invertebrates, along with direct soil ingestion during foraging activities. Dietary intake modeling typical for ecological risk assessments is the recommended approach for an evaluation of potential risks to wildlife species where PFAS exposure occurs primarily via dietary uptake from bioaccumulation pathways. Dietary intake modeling uses relevant exposure factors for each receptor group (terrestrial birds, terrestrial mammals, aquatic-dependent birds, and aquatic mammals) to determine a total daily intake (TDI) of PFAS via all potential exposure pathways. This approach requires determination of concentrations of PFAS in dietary items, which can be obtained by measuring PFAS in biota at sites or by using food web models to predict concentrations in biota using measured concentrations of PFAS in soil, sediment, or surface water. Food web models use bioaccumulation metrics such as bioaccumulation factors (BAFs) and biomagnification factors (BMFs) with measurements of PFAS in abiotic media to estimate concentrations in dietary items, including plants and benthic or pelagic invertebrates, to model wildlife exposure and calculate TDI. Once site-specific TDI values are calculated, they are compared to known TRVs identified from toxicity data with exposure doses associated with a lack of adverse effects (termed no observed adverse effect level [NOAEL]) or low adverse effects (termed lowest observed adverse effect level [LOAEL]), per standard risk assessment practice<ref name="USEPA1997"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Recently, Conder ''et al.''<ref name="ConderEtAl2020"/>, Gobas ''et al.''<ref name="GobasEtAl2020"/>, and Zodrow ''et al.''<ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/> compiled bioaccumulation modeling parameters and approaches for terrestrial and aquatic food web modeling of a variety of commonly detected PFAS at AFFF sites. There are also several sources of TRVs which can be relied upon for estimating TDI values<ref name="ConderEtAl2020"/><ref name="GobasEtAl2020"/><ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/><ref>Newsted, J.L., Jones, P.D., Coady, K., Giesy, J.P., 2005. Avian Toxicity Reference Values for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(23), pp. 9357-9362. [https://doi.org/10.1021/es050989v doi: 10.1021/es050989v]</ref><ref name="Suski2020"/>. In general, the highest risk for PFAS is expected for smaller insectivore and omnivore receptors (e.g., shrews and other small rodents, small nonmigratory birds), which tend to be lower in trophic level and spend more time foraging in small areas similar to or smaller in size than the impacted area. Compared to smaller, lower-trophic level organisms, larger mammalian and avian carnivores are expected to have lower exposures from site-specific PFAS sources because they forage over larger areas that may include areas that are not impacted, as compared to small organisms with small home ranges<ref name="LarsonEtAl2018"/><ref name="ConderEtAl2020"/><ref name="GobasEtAl2020"/><ref name="Suski2020"/><ref name="ZodrowEtAl2021a"/>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Available information regarding PFAS exposure pathways and effects in aquatic life, terrestrial invertebrates and plants, as well as aquatic and terrestrial wildlife allow ecological risk assessment methods to be applied as outlined by USEPA<ref name="USEPA1997"/> to site-specific PFAS risk assessments. Additionally, food web modeling can be used in site-specific PFAS risk assessment to develop initial estimates of dietary concentrations for aquatic and terrestrial wildlife, which can be confirmed with tissue sampling programs at a site.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==PFAS Risk Assessment Data Gaps==

| |

| − | There are a number of data gaps currently associated with PFAS risk assessment including the following:

| |

| − | *'''Unmeasured PFAS:''' There are a number of additional PFAS that we know little about and many PFAS that we are unable to quantify in the environment. The approach to dealing with the lack of information on the overwhelming number of PFAS is being debated; in the meantime, however, PFAS beyond PFOS and PFOA are being studied more, and this information will result in improved characterization of risks for other PFAS.

| |

| − | | |

| − | *'''Mixtures:''' Another major challenge in effects assessment for PFAS, for both human health risk assessments and environmental risk assessments, is understanding the potential importance of mixtures of PFAS. Considering the limited human health and ecological toxicity data available for just a few PFAS, the understanding of the relative toxicity, additivity, or synergistic effects of PFAS in mixtures is just beginning.

| |

| − | | |

| − | *'''Toxicity Data Gaps:''' For environmental risk assessments, some organisms such as reptiles and benthic invertebrates do not have toxicity data available. Benchmark or threshold concentrations of PFAS in environmental media intended to be protective of wildlife and aquatic organisms suffer from significant uncertainty in their derivation due to the limited number of species for which data are available. As species-specific data becomes available for more types of organisms, the accuracy of environmental risk assessments is likely to improve.

| |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| Line 96: |

Line 58: |

| | | | |

| | ==See Also== | | ==See Also== |

| − | [https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-studies/index.html Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) PFAS Health Studies]

| |